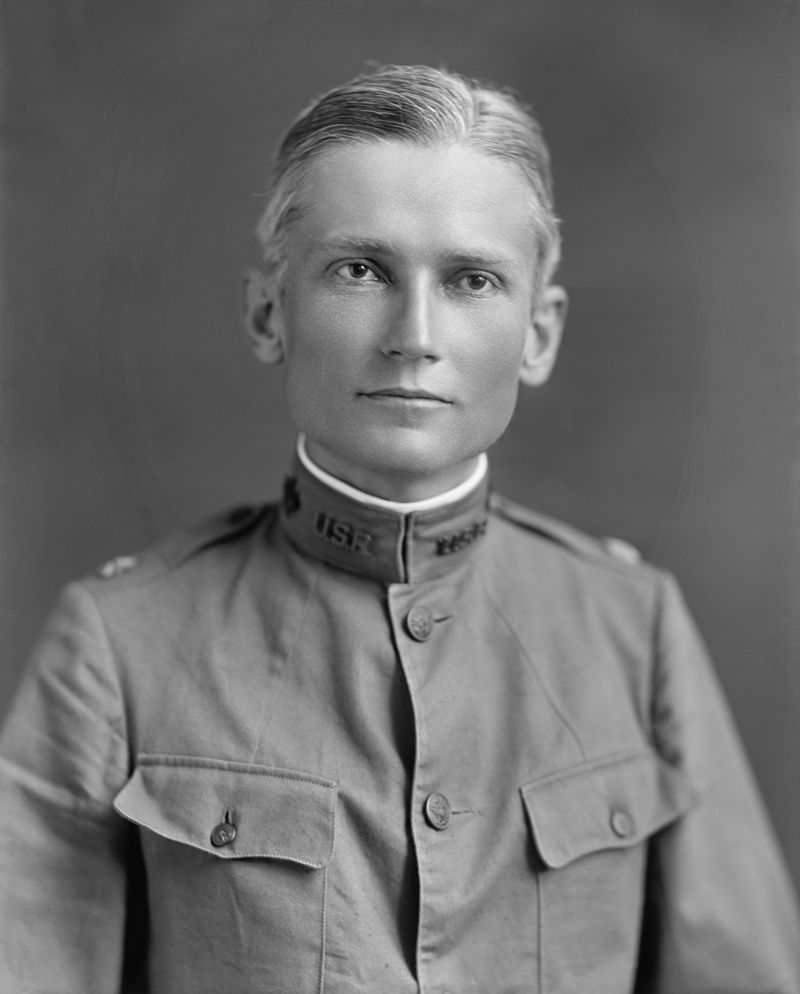

Hiram Bingham

Hiram Bingham (Honolulu, 1875-1956) was an academic, explorer, soldier and American Senator, considered to have discovered Machu Picchu.

His first contact with Latin American history was in 1900 at the University of California in Berkeley, where he studied. His bachelor’s degree was obtained at Yale University and later, he obtained a doctorate at Harvard University, in 1905.

In 1911, he visited Machu Picchu for the first time, although he did not make it public until he obtained funding from Yale University and the National Geographic Society to return to Machu Picchu in 1912, 1914 and 1915.

In 1913, he published the discovery in the National Geographic Society magazine along with photographs he had taken. At that time, the discovery of Machu Picchu was wildly publicized, and he became an international celebrity. In 1948, he published his most famous work: “Lost City of the Incas”, which has become a best seller since its publication.

Hiram Bingham, the Explorer

Hiram Bingham was not an archaeologist. He had not even practiced archeology before. He was an explorer who was fascinated with the history of Latin America.

His obsession with the territory was consolidated in 1908 when he traveled to Santiago de Chile to participate in the Pan-American Scientific Congress. On his return to the United States he stopped in Lima, where he was convinced to visit the City of Choquequirao.

Bingham had the spirit of an explorer and was obsessed with the possibility of finding ancient unexplored Inca cities. Thus, in 1911, he made his first trip to Peru determined to discover the last capital of the Inca Empire.

Machu Picchu

Machu Picchu has become the biggest tourist attraction in Latin America. This archaeological monument is known throughout the world. Bingham has been recognized as the first person to bring the world’s attention to the site.

Bingham was actually looking for the city of Vilcabamba, not Machu Picchu. He had been told that it was the true hidden capital of the Inca Empire. It was known that there was a hidden city that was the last inhabited Inca settlement around Cusco, but it was not known where it was.

In July 1911, he made camp in the Sacred Valley of the Incas (the Sacred Valley) and with several local guides he advanced through the valley’s jungle. He was accompanied by Melchor Arteaga, a Peruvian expert in the area, as well as two British missionaries, Thomas Payne and Stuart McNairn. Several explorers from Cusco were also part of the expedition: Enrique Palma, Gabino Sánchez, Agustín Lizárraga, who claimed to know the place.

The Sacred Valley of the Incas was inhabited by the Incas decades before Machu Picchu. Evidence of this can be found in vestiges like Pucaras (fortifications) and Tambos (rest stops on the long network of roads that connected the Inca Empire) that are found along the Vilcabamba mountain chain. At that time, Bingham verified the importance of this area given the hundreds of ruins and vestiges of the Inca Empire that existed in the Sacred Valley.

Melchor Arteaga only spoke Quechua, but he managed to lead them to the place he had understood they were looking for. The inhabitants of the place called it “Machu Picchu”, which translated into English is “ancient mountain”, probably alluding to its former inhabitants. That is why Hiram Bingham thought that what he had found was Vilcabamba, which he called “The Lost City of the Incas” and not Machu Picchu.

Once they reached Machu Picchu, Bingham soon realized the spectacular discovery he had made. An extraordinary example of engineering and architecture, totally unknown to the western world of that time.

Bingham’s amazement with the citadel is palpable in this excerpt from 1913:

“The superior character of the stone work, the presence of these splendid edifices, and of what appeared to be an unusually large number of finely constructed stone dwellings, led me to believe that Machu Picchu might prove to be the largest and most important ruin discovered in South America since the days of the Spanish conquest.”

And he was not without reason. To this day, thousands of people admire Machu Picchu daily.

The expedition party cleared the ruins of weeds, studied the area, and took photographs that were later published by the National Geographic Society magazine. Hiram Bingham introduced Machu Picchu to the world.

Extended Controversy

Years later, however, it was found that Hiram Bingham illegally took hundreds of archaeological pieces to Yale University and others to the private collections of his expeditions’ sponsors. In 2008, the Government of Peru claimed from the US -Government some 40,000 archaeological pieces irregularly extracted from the site.

Apparently, Bingham took the pieces before making the discovery known and made it public when there were no longer any pieces left in the place. This practice was very common among the European explorers of the 19th and 20th centuries in Egypt, Greece and Mesopotamia, the great civilizations of the ancient world.

Even today, these pieces can be found in major European museums such as the British Museum or the Louvre. The pieces were never returned, despite claims from the countries where they were found.

The case of Hiram Bingham and Machu Picchu is still in litigation. Yale University has complied with returning the pieces it had, but several archaeologists have pointed out that there are many other pieces that are in the hands of private individuals.

Previous Discoveries of Machu Picchu

Today, we know that before Hiram Bingham there were other western explorers who knew the city, but did not divulge its existence.

The British missionaries who accompanied Bingham said that they had already been there in 1906. A German explorer named Augusto Berns bought lands very close to Machu Picchu in 1860, because of the “importance of the ruins”. And there is a map from 1874 which includes a drawing of the famous citadel.

The National Geographic magazine itself currently describes Hiram Bingham as having “rediscovered” Machu Picchu on the expedition they financed.

Feud Between Americans and the British

The 19th century was the century of discoveries. Great ancient civilizations were discovered by European explorers. Many of them were not archaeologists or historians, but merely lovers of the unknown, of history and of the most advanced ancient civilizations of mankind.

The exploration of remote places was a huge source of adventures and advances in scientific knowledge. The explorers were admired and respected in the western world. Lord Carnarvon had become an international celebrity for funding and active participation in the discovery of Tutankhamon’s tomb in the Valley of the Kings, Egypt.

The explorations of ancient civilizations became an activity coveted by British, Italians, French and Germans who competed with each other to discover unknown civilizations and archaeological monuments, as well as to seek fame and worldwide respect.

However, the United States arrived late to that race for discoveries. Hiram Bingham was the first American star in a field dominated by the British. His discoveries were published and highly valued in the United States, placing him firmly in the category of celebrities.

Indiana Jones

It cannot be guaranteed that the character of Indiana Jones was inspired by Hiram Bingham; however, there are many similarities between reality and fiction.

Neither of them were archaeologists or historians, they were explorers. Both were looking for an ancient civilization in the jungle. In his first film, Indiana Jones looked for “the lost ark”, while Bingham looked for “the lost city”.

The physical aspect of the character was also similar to the most famous photos that are conserved of Bingham: tall, fedora hat, boots and dusty. Both characters pursued the discovery of vestiges of the past with real passion.

Senator Hiram Bingham

Ten years after the discovery of Machu Picchu, Hiram Bingham became interested in politics. Helped by the fame he had acquired from the discovery of Machu Picchu, he became very popular in the United States.

In 1922, he was elected Lieutenant Governor of Connecticut. In 1924, he resigned his position to replace a United States Senator whose seat had become vacant. In 1926, he was re-elected Senator. He died in 1956.