Hain Ceremony

Winter of 1923

It was winter in Tierra del Fuego. The land was blanketed with ice and snow. The days were racing by, with darkness lingering late in the morning and arriving early in the afternoon. The men had gathered far from the women to decide on a place for celebrating a sacred ceremony: the Hain. They sensed that this would be one of the last times they would be holding this rite, since unknown diseases were rapidly decimating their people, and the advent of sheep ranching was destroying their way of life. Amputated from their cultural wealth, the Selk’nam, or Onas -ancient hunters and gatherers- endeavored to preserve their customs. The youths, now mostly employed as ranch hands, scarcely knew their traditions, and the clans were unable to move about freely as they once had in this territory that had become fenced in by the white man. Even so, the old ones fought to keep alive “the mystery and joy of that which was slipping through their fingers.

Their new life did not have room for the Hain’s creative and theatrical ritual, full of life and fantasy, of drama and fun.”I The men initially set up their camp for the Hain near the northeast shore of Lake Fagnano, but soon decided to search for another site better sheltered from the wind. Once the huts had been disassembled and, along with the equipment, packed in leather bags, the caravan headed east. In front were the men, wearing full- length guanaco capes, and carrying bows, arrows and tools. Behind were the women and children, also wearing capes, but bearing bundles on their backs.

After walking several hours through forests and marshland, the group pitched camp only a few steps from Pescados Lagoon. Each family erected a hut and lit a fire in the center. In front of the camp was a broad, somewhat raised meadow- a true stage for the presentation of the Hain rituals.

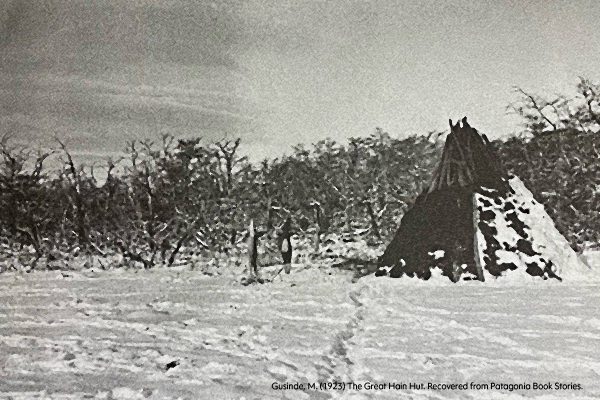

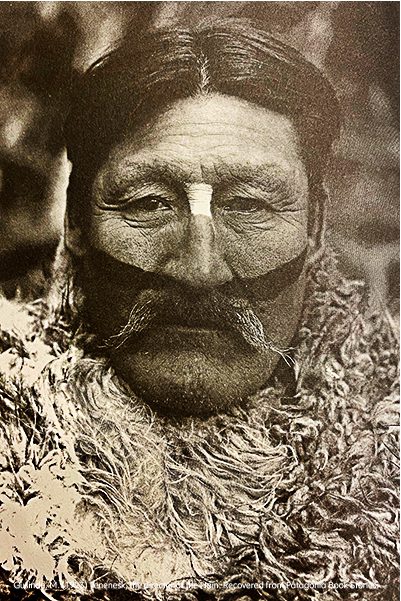

Here, some two hundred paces from the camp would be built a hut bigger and higher than all the rest. The backdrop for the “Great Hut” was a snow-covered forest. Tenenesk, who best remembered and kept his clan’s customs, directed the construction of the Great Hut and later on, the Hain ceremony. After all had eaten, he went with his nephew, Toin, to the far end of the meadow. There they met up with the other men to begin their work. Some leveled the site, others dragged logs, and the rest carefully piled up clumps of turf and moss. Following a venerated tradition, the men felled about fifty tall, large-diameter trees. Tenenesk chose seven- the biggest ones–and had them used to make a tepee-like structure. The framework was completed with slenderer trunks and then covered with the collected turf and moss. Finally, grass was placed on the floor, and a meter- wide ring bordering the inside wall of the Hut was marked off where the initiates would sit. The Hain Hut was finished just as it had always been finished since time immemorial, under the expectant gaze of the women, who watched from the camp.

That night, while seated with all of the men around a fire in the Great Hut, Tenenesk explained that their secret ceremony had first been celebrated after the “great revolt.” Slowly, deliberately, he told them that the seven most renowned shamans from different regions had built the original Hain. Each had gone into the forest, cut down a tall tree, and had brought it to the site of the Hut. He concluded by saying, “All of them were powerful men, and were the ones who founded this secret celebration. That is why those seven posts must be raised first.”‘2

Journey to the world of the initiates

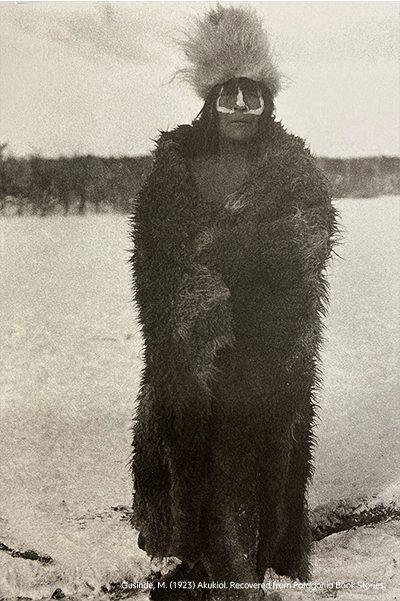

The next day–May 22, 1923- -Akukiol got up before dawn and went just outside her dwelling. All of the huts were located near by and faced the Hain Hut, whose entrance was hidden in the back. Akukiol began singing a chant to bring the new day. The rest of the women took up positions outside of their huts and joined in. Just as the sun began to tenuously illuminate the threatening sky, the women started another chant, to welcome it or to mark the beginning of the Hain ceremony’s first day. They continued with their song rituals throughout the days and weeks that this sacred occasion lasted.

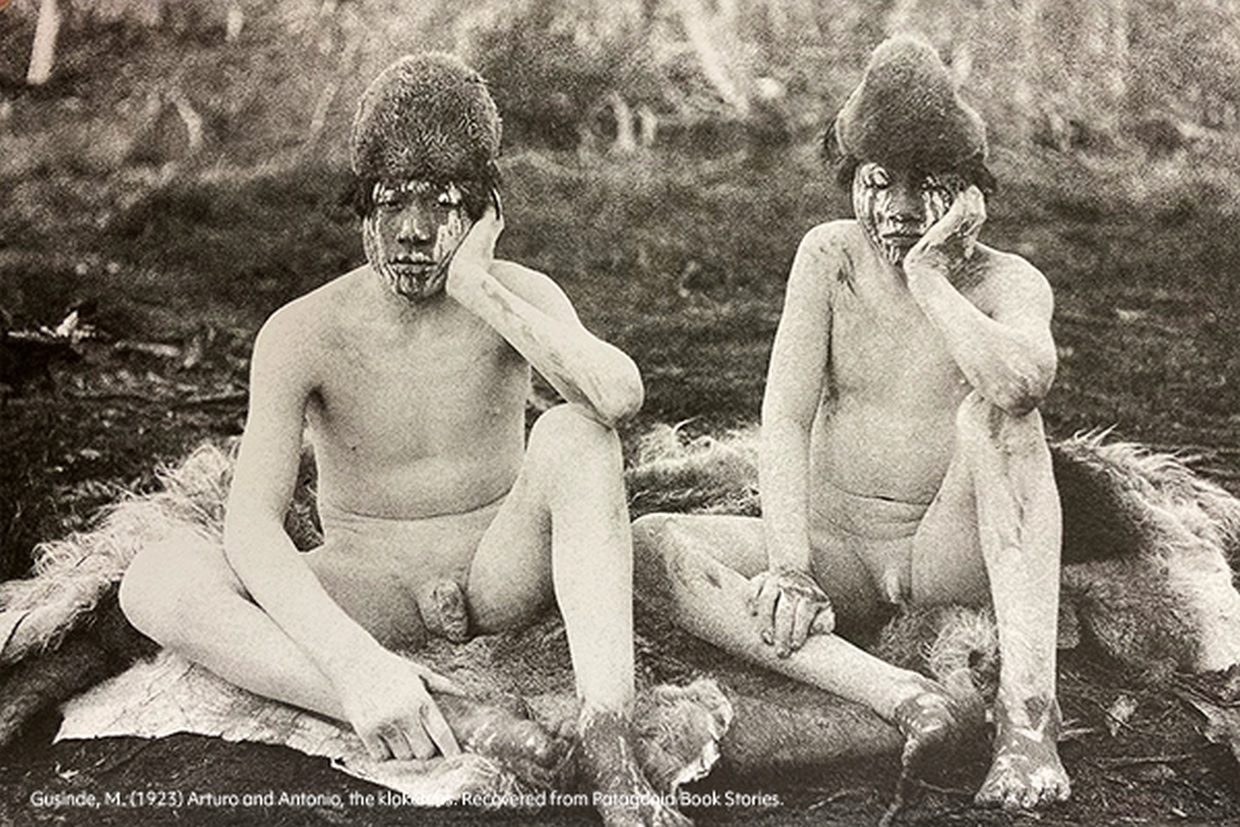

Clouds swept in, chilling the damp morning air. This time, only two adolescent boys would take the solemn journey to the world of the initiates, or kloketens: sixteen-year-old Arturo, the son of Akukiol and Halimink; and fourteen-year-old Antonio, the son of Nana. Both anxiously awaited the arrival of their supervisors. Meanwhile, the women prepared red paint from an ocher clay for the designs that would cover their bodies.

In the afternoon, two supervisors escorted the kloketens to Akukiol and Halimink’s hut. The mothers, deeply worried and upset, nervously caressed their sons. Other women from the camp appeared, singing a new chant. The supervisors removed Arturo’s and Antonio’s fur capes, then stretched their arms above their heads and tied them to a limb hanging inside the hut. Afterward, they washed their bodies, which when almost dry, were daubed completely with red paint made from ocher clay, water and a bit of guanaco fat.

Meantime, the mothers painted three vertical white stripes on their own faces to convey that they would be separated from their sons for a long period of time. Only Akukiol also had a crowning, trian- gular guanaco fur headdress, the symbol of the kai-kloketen the leading woman during the Hain ceremony, the mother of the eldest kloketen candidate.

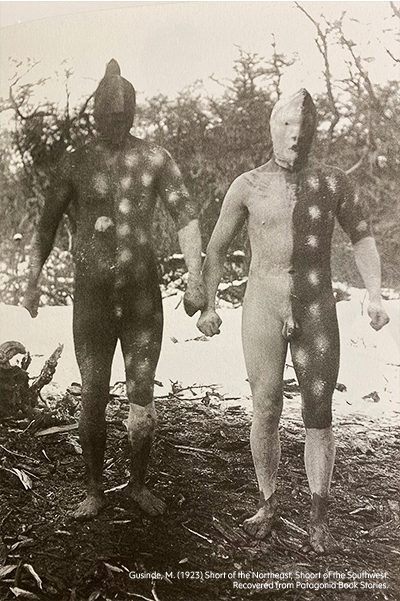

While the rest of the women sang and joyfully painted their torsos with red paint, the men quietly slipped out of the camp and entered the Great Hut, a place forbidden to the women and children. Suddenly, before the expectant onlookers, two Shorts, whose bodies were painted the color of white ash, appeared from both sides of the back of the Great Hut. They wore an adherent red mask with small openings for their eyes and nose; a broad, red stripe descended from their necks all the way down to their feet. With rigid steps, these evil spirits began moving slowly across the meadow. Abruptly, they jumped, holding their arms tight against their sides, their fists clenched, and shaking their heads from side to side. The men inside the Great Hut let out a frightening yell. With the first of a seemingly endless succession of rites, dances and games representing the myths that explained the world to the Selk’nam, the Hain ceremony had began.

The kloketens were taken into the Great Hut, where the men were standing in a semi-circle staring at the fire. Arturo’s and Antonio’s capes were removed while Halimink ordered them to look upward. The supervisors grabbed their heads, jerked them back, and held them in that position. Suddenly, the Shoorts seemingly sprang from the fire and started attacking the kloketens. Bewildered, the kloketens began wrestling with their opponents, not fully understanding the reasons for the fight nor the terrifying yells of the men. Finally, when the kloketens were exhausted and at their wits’ end, the supervisors ordered the fighting to stop, and the initiates, to remove each Shoot’s mask. Trembling with terror, they gingerly touched, then raised the masks and discovered to their amazement the men’s secret: the Shoorts and all of the Hain’s other malicious spirits were not supernatural beings from the underworld as they had always imagined, but men of their own clan.

The Shoorts had to frighten the kloketens out of their wits to demoralize them from the outset so that later on they would submit willingly to all of the instructions and commands of the men who were present. This was their lesson and the secret that could never be revealed to the women.

The spirits–always wearing masks, always painted with unalterable white, black and red symbolic designs on their nude bodies- appeared daily throughout the length of the ceremony. Thus, they were able to watch over the mythical world constructed by the Selk’nam men–a realm that would forever remain an enigma to the women.

After the arduous fight with the Shorts, Tenenesk gave each kloketen a kochil, a triangular guanaco fur headdress, as the first sign of his adult status. In addition, he gave them a small stick they could use to scratch their head during those long hours in which they had to sit in a special position while receiving their instruction and training. Inside the Great Hut, they had to sit with their left palm against their cheek while supporting their left elbow on their left knee, and look intently at the fire. They were not allowed to laugh or yawn, could only talk when asked a question, and were repeatedly warned to not tell anyone, especially the women and children, what went on inside that supernatural space.

Following the initial dramatic and most important part of the initiation ceremony came another crucial step: spending the night in the forest, which to the youths was another new and formidable challenge. It was in that ancestral place, the same journeyed through by their forebears, where the kloketens had to be trained for endurance, self-control and rational thinking. During long walks, they had to face new fears and become acquainted with hardship. And while now, their people were not allowed to freely hunt guanacos-once a major source of meat, clothing and other essentials–they were not true Selk’nam unless they were proficient with the bow and in tracking animals of prey.

The hunter of images

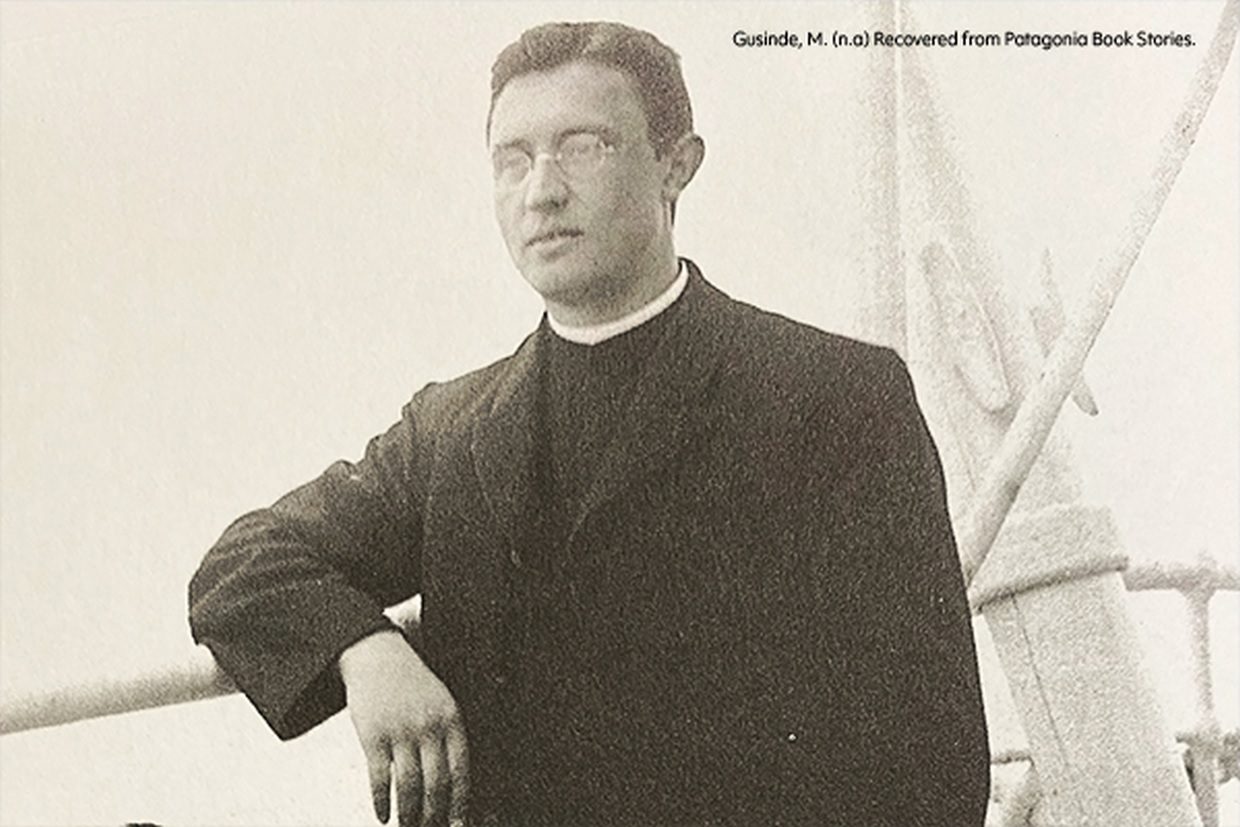

When the kloketens were first escorted to the Great Hut, a third man accompanied them. After the fight had finished with the Shoorts, Tenenesk also gave him a kochil. “You already know these things; you were a kloketen among the Yamana. » So said Tenenesk to his German friend, Martin Gusinde, the only white man to witness the Hain ceremony in 1923.

This was not the first time that the foreigner had visited the land of the Selk’nam. An ordained priest of the Society of the Divine Word and an anthropologist, he had arrived in Chile in 1912 at the age of 26 to teach at the Liceo Alemán (German School) in Santiago. From the very beginning, he collaborated with the ethnographic and anthropological research projects of importan local and European educational institutions.

Gusinde’s friendship with the Sell’nam commenced in the summer of 1919 when quite by chance he met Tenenesk and his group while camping near the head of Lake Fagnano. After a short visit, he entered the local folklore as Mank’acen, or the Hunter of Images- the manner in which he was perceived by those he” stalked” with his camera.

In the first part of April, in 1923, Gusinde visited them again, hoping to be invited to an initiation ceremony, as Tenenesk had insinuated to him earlier. After almost a month among them, Gusinde saw no sign that Tenenesk intended to keep his promise. At his insistence, the men responded that the imperative to obtain food did not allow for an uninterrupted presentation of the Hain ceremony. “We are only a handful of men,” they said. Realizing the magnitude of the problem, Gusinde decided to help them obtain the necessary staples. He gave them a total of three hundred sixty sheep he acquired from a Salesian missionary ranch, and promised to provide each family with a small amount of tobacco and an Argentine peso every three days throughout the ceremony.

During the almost two-month-long ritual, Gusinde untiringly recorded, catalogued and photographed all that he witnessed. As an initiate, he participated in the conversations that took place inside the Great Hut. With the others around the fire, he listened as Tenenesk told the myth explaining the origin of the Hain- a custom that in addition to initiating the kloketens, helped to preserve the patriarchal society and keep the women under the men’s domination.

Long ago, before the “great revolt,” the women, led by Moon- woman, ruled the men. They made them hunt, care for the children and perform all of the household chores. Every so often, Moon decided to celebrate a Hain so that the young women could be initiated into adulthood, and also to make sure the men remembered that the spirits and the divinities were the women’s steadfast allies. For this ceremony, they painted their bodies and used masks to impersonate the spirits who arose from the depths of the earth or descended from the heavens. Through their game of pretense, they sought to deceive the men, who were awed by a spectacle that filled them with both admiration and terror. On one such occasion, Sun, Moon’s husband, accidentally learned of the hoax when he happened across two women who were removing their paint while making fun of the men they had frightened. Shocked and outraged, Sun told the men about his discovery, and prepared to lead them in a great rebellion. And that was how the men came to attack the women and kill all those old enough to know the secret. After receiving punishing blows from her husband, Moon fled to the heavens bearing great scars on her face that can still be seen at night when the moon is full. Sun struck out in hot pursuit, but was unable to catch her, and continues to pursue her to this day; thus day and night were born. When the girls who had been spared during the rebellion reached maturity, the men celebrated their first Hain. In the same way that they had been dominated by the female power, the men now subjugated the women.

The farewell

On July 10, 1923, the men filed out of the Great Hut and headed over the meadow to the camp, where they were joyfully received by the women. The ceremony had ended. Days earlier, Martin Gusinde began showing signs of scurvy and anemia. He told Tenenesk that he needed to cross the mountains to reach Harberton Ranch- owned by the Anglican missionary Lucas Bridges-on the Beagle Channel, to rest a while, and then return to Santiago, Chile. To Tenenesk, the idea was ludicrous: not even a Selk’nam would have the courage to cross the mountains in winter. His mind made up, Gusinde announced to him that Toin and his friend Hotex, had agreed to accompany him. Exasperated by the stubbornness of his guest, Tenenesk warned him one last time:

A dense snowstorm and winds of hurricane force will surely strike while you’re crossing. If, besides you, your companions also perish, just think of that! You’ll be responsible, only you, for not having heeded my warning. You don’t think of your father, nor of your mother who are waiting for you. Your stubbornness really pains me. I’ve warned you! We’ll never see each other again!’ Gusinde quickly prepared for his trip. He bid them all farewell, eternally grateful for their friendship and trust, and promised them that he would be back soon. The trip to Harberton Ranch lasted almost six days. He never once forgot Tenenesk’s words of warning. The landscape was bleak and frozen, and each day abandoned them to their luck after only a few hours of light. Exhausted and half-frozen, Gusinde and his Selk’nam companions reached their destination.

Martin Gusinde never returned. During the winter of 1924, Tenenesk, his wife Kauxia, and Arturo died, victims of a major measles epidemic. By then, Gusinde was in Vienna, beginning his doctorate in Ethnology, Physical Anthropology and Prehistory. Five years later, in 1929,Akukiol and her husband Halimink died, also from measles. Martin Gusinde died in Vienna at the age of 83, having published most of his writings and photographs from his expeditions to Southern Patagonia.